शौचात् स्वाङ्गजुगुप्सा परैरसंसर्गः॥४०॥

shouchaat = from cleanliness; svaanga = one’s body; jugupsaa = distaste; paraiH = with others; asaMsargaH = cessation of union or contact

Sw. Satchidananda

"By purification arises disgust for one’s own body and for contact with other bodies"

When ‘shaucha’ is observed, we realize that our body is impure – breath gives out carbon dioxide, skin discharges perspiration etc. We can make all the efforts to cover external impurities by powder, lotion, perfume etc., but the essential impure nature of the body cannot be changed. The time we spend on artificially beautifying the impure body can be effectively spent on japa and meditation to cleanse the inner body.

When we realize that our own body is impure, how can we feel attracted to another body which is equally impure? Many people misinterpret and misunderstand the Tantric system of yoga to mean purely sexual union for self-realization. Tantra talks about Shiva and Shakti as being the male and female aspects of the same individual. In Hatha Yoga, we talk of Sun and the Moon. In the word Hatha, Ha represents the Sun (solar plexus) and Tha, the moon (base of the spine). In yogic terms it implies the meeting of prana and apana breaths. In the Bhagavad Gita also there are shlokas emphasizing the meeting of these two breaths (shlokas 15.14, 4.29).

Bryant

"By cleanliness, one (develops) distaste for one’s body and the cessation of contact with others."

The yogi reflects on the nature of his own body which remains unclean despite all the external and internal cleaning that one might do. How, then, can one think of intimate contact with another body which may be even more unclean?

There is the story of a king who, becoming thirsty after hunting in the forest, approaches a secluded hermitage in quest for water. He is greeted by a beautiful but spiritually edified young maiden who had been raised as a fully enlightened yogini by the resident sage of the hermitage. Overcome by desire for this beautiful maiden, the king propositions her. Deciding to enlighten the lusty king as to the realities of bodily yearning, the maiden requests him to return within a month, at which time she will allow him to taste the nectar of her beauty. During this period, however, the maiden takes laxatives and purges, and collects all the resulting vomit, urine, feces, and other discharges in earthen pots. When the king returns after the stipulated period, he is greeted by the maiden, now haggard and wasted and a shadow of her previous self. Upon asking her what had become of her beauty, she presents the king with the earthen pots with their rancid contents and indicates that therein lay the juices of her beauty.

No matter how hard one works to present the body as an erotic object – cleaning with soap and water; putting on makeup, cosmetics and attractive clothing; subduing the natural odors with perfume etc., body can still emit embarrassing odors and sounds at the most romantic moments! The yogi begins to see this reality of the body as consisting of obnoxious substances, and ceases to see the body of others with erotic interest. The yogi conveys love for others through compassion, spiritual exchanges, expressions that rise above physical sensuality.

From an ultimate, metaphysical perspective, the yogi sees both feces and fragrance as simply transformations of the three gunas of Prakriti.

Discussion

According to most commentators, this sutra refers to the result of external cleanliness of the body. The next sutra (2.41) refers to the result of internal or mental cleanliness.

How does one practice shaucha?

A brief mention of the techniques for both internal and external cleansing was made during the discussion on sutra 2.32 which defines the five Niyamas.

At the first reading, the word "jugupsa" (disgust) seems rather strong for the human body which is also referred to as the "temple" where the pure soul resides. Moreover, it is mentioned in our scriptures that one can attain liberation only when one takes birth in this human form which automatically entails having the physical body. So, how can such a body be labeled as being "disgustful"?

On a deeper reflection, one begins to realize that Patanjali here is talking about a yogi who is deep on a spiritual path and necessarily has to discard any identification with the physical body. Any such attachment to the physical body can only become an obstruction toward spiritual pursuits. In order to aid in that detachment from the body, Patanjali here discusses how you can develop a distaste for one’s body as you go through a deep cleansing process.

(Commentary by Kailasam Iyer)

YSP II- 40 The cognitive faculty (of a yoga practitioner) develops a disgust for the organic part of life through the cleansing of mind and avoids association with others ( of unlike minds).

These are strong words to describe a pursuit. There is no soft-pedalling this sutra and its intent. Misunderstanding can be avoided only by keeping the context in view while we navigate through the meaning. Ashtanga Yoga is a progressive methodology for cultivating sustained discrimination of intellect for the purpose of eliminating all differentiations of the Being, perceiving the Being as the ( last) sole impression in the mind, and then losing that impression as well to be in a state of nischalanam or absence of disturbance. In the Sankhya system of evolutes, mind receives sensory information, recalls from memory, and processes the composite to facilitate the ego to develop a subjective awareness of experience. A trained sathvic aspect of Buddhi can see through this mire and can display the Being as unmixed with life’s struggles. Recognition of this purity changes forever the outlook of the sadhaka.

Mind is where everything happens and for the Being to be perceptible in it the mind has to be in a state of cleanliness. Experience can EITHER be enjoyed by the body OR be contemplated upon in the mind for release from attachment ( YSP II- 18). The competition between the two in a philosophical sense is clear. Cleansing the mind by a rigorous, sustained practice of yamas ( YSP II- 35 to 39) increases the fervor to keep the body and its desires at bay to avoid further contamination. The spirit wants to soar but the body weighs it down.

Colin McGinn, an analytical philosopher , has examined the emotion of disgust to probe the content of that emotion. My summary of his treatment is that Consciousness has nothing inside itself to indicate its own mortality and when it discovers the mortality of the body which supports consciousness, it feels betrayed and is disgusted by the body.

I am sure there are other ways of understanding this very strong statement by Patanjali; but, the understanding becomes vivid in one’s mind ONLY upon meditation over an actual experience in the manner recommended by YSP in II-19 by taking experience through the four hierarchical stages of the model of the evolutes repeatedly until it becomes a habit.

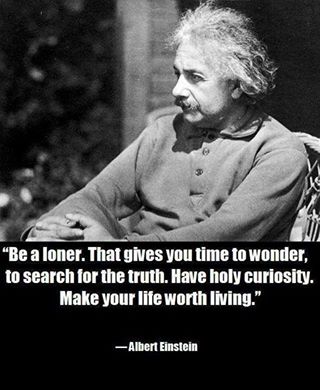

The desire for dissociation from unlike minds is a logical next step. Once the determination is made to pursue a path of enlightenment in a particular way, other minds which offer alternatives, arguments, temptations, etc., are impediments on one’s path. The interactions necessary for existence in day-to-day world are obstacles to an ascetic. Lord Krishna ( Vyasa ) uses the words arathihi ( distaste) and janasansadhi ( mixing with people) in BG XIII-10 in the same context. The quest is private and lonely. Einstein recognized the need for aloneness in times of concentration. Please see attachment.

Disgust for bodily needs and separation from crowds are external manifestations of an ascetic life. The next sutra describes the steady, slow, progressive changes which gradually develop internally in the mind of an ascetic.

Leave a Reply